I just couldn’t breathe. Four steps, five steps, time to breathe. Four steps. Breathe. An urge to lie down and just close my eyes, just for a short nap. And that was the moment I knew the mountain had won. “One of the most difficult hikes in the world”, the Drakensberg Grand Traverse, multiple days in the mountains without a clearly marked trail, without resupply stations, and -apart from the local shepherds- little or no other humans … had gotten the best of me. No solo, unsupported Drakensberg Grand Traverse for Polle this year. Drakensberg 1. Polle 0.

The Drakensberg escarpment and the Drakensberg Grand Traverse.

Let’s take a step back. The Drakensberg escarpment and the Drakensberg Grand Traverse.

If you’ve ever been to South Africa, you know the Drakensberg. Or at least, you’ve seen it. The Drakensberg escarpment stretches for more than 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) from North to South with peaks up to 3,482 meters (Thabana Ntlenyana) and is therefore hard to miss. It is a vast mountain range, partly in Lesotho, partly in South Africa.

The Afrikaans name Drakensberge comes from the name the earliest Dutch settlers gave to the escarpment, namely Drakensbergen, or Dragons’ Mountains. And it isn’t too difficult to imagine why – the spikey peaks resemble the back or teeth of dragons (depending on your personal preference).

And what about the traverse? Well, the Drakensberg Grand Traverse (DGT for friends) is the trail that covers the key peaks of Drakensbergen, in the mountainous region between South Africa and Lesotho. 6 peaks, a collection of sheep- and shepherd trails … making it a route of approximately 220-250 kilometers. Approximately, as the “trail” is a loose collection of unmarked trails, with multiple options to get from peak to peak. That, the fact that the weather is notoriously unpredictable and fast-changing (the only constant is the fast change), and that the area is remote without options to re-supply, makes it, as some people say, “one of the most difficult trails in the world”.

Day -x. Preparing for a formidable adversary.

I will skip the story of the months-long preparation of the DGT for this post (this post in itself is lengthy enough already); I created a separate post for that on planning and preparing for the Drakensberg Grand Traverse. Let’s say I spent a fair amount of time preparing.

Day 0. Meeting the mountains

My story starts the moment my flight landed in Johannesburg. After a comfortable overnight flight with my friends of Air-France KLM, I arrived at O.R. Tambo International Airport in Johannesburg. I had a busy morning ahead. Get some cash. Get food for the morning and lunch. Check, check, double-check all devices (phone eSIM, Garmin InReach devices). Pick up the gas cannisters I had delivered at one of the airport hotels (thanks Kelly and Kelly’s mom for the help). Change into my hiking clothes. Leave redundant gear, “travel-clothes”, bags, and other stuff I did not need on the trail at the same airport hotel. And then I was ready to go for the long ride to Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge, which would be my end point for the day and the starting point for my hike tomorrow (well … the transfer to the starting point of the hike … but you get the idea).

Via a fellow Dutchman (thanks Nick!) who hiked the Drakensberg Grand Traverse earlier this year, I had gotten in contact with Tau, a resident of Phuthaditjhaba, the city in the valley below the Sentinel peak and the mountain lodge. He had agreed to take me from O.R. Tambo airport in Johannesburg to the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge. He had been super flexible and responsive leading up to the trip, and now he and one of his friends would pick me up. Seeing them arrive at the arrivals pickup made me smile … two friends in a small, cosy silver Toyota that barely fit the three of us and my huge backpack. But it worked surprisingly well. The guys were upbeat, friendly, and professional, and we had a smooth drive southwards towards the Drakensberg

Later in the afternoon, after approximately a 5-hour ride, we arrived at the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge, just in time to meet the mountains for the first time. From the lodge, you can clearly see the Sentinel and other iconic rocks. It felt overwhelming. The mountains seemed huge, almost out-of-this-world. But above all, I was excited. Finally, we met. Finally, I would start my Drakensberg Grand Traverse.

Day 1. The prelude. Sentinel Car Park and the Chain Ladders.

I had a decent night of sleep at the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge. I had not expected too much beforehand, but it had been a pleasant surprise. The Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge turned out to be a convenient and comfortable base for adventures, small and big, in the Northern Drakensberg area. Friendly staff, really decent dinner options, and (basic, yet decent) English breakfast. The team even made me a breakfast/lunch bag even as I had to leave early, before the breakfast was open, to catch my transfer to the start, the Sentinel Car Park.

The transfer was a proper 4×4, which I had come to appreciate during last year’s South African safari. On board, nine tourists and a local driver. Four twentysomethings from South Africa who were doing a boys’ trip with overnight sleep at the hut at Tugela Falls. An experienced German couple who wanted to do a day hike to the falls. A Belgian guy who had left his wife at the lodge for the day with similar plans. And me.

As soon as we’d left the lodge, the road turned bumpy. Big rocks. Mud. Gravel. Large pools of water. For about 40 minutes, the driver tried his best to navigate all the pits, rocks, and other elements of nature until, out of seemingly nothing, the road turned back to a normal road again, exactly the same kind of road that led up to the mountain lodge. Later, I heard that the government had promised to fix the road year after year after year, but that this still wasn’t done … and that the only solution for now was 4x4s.

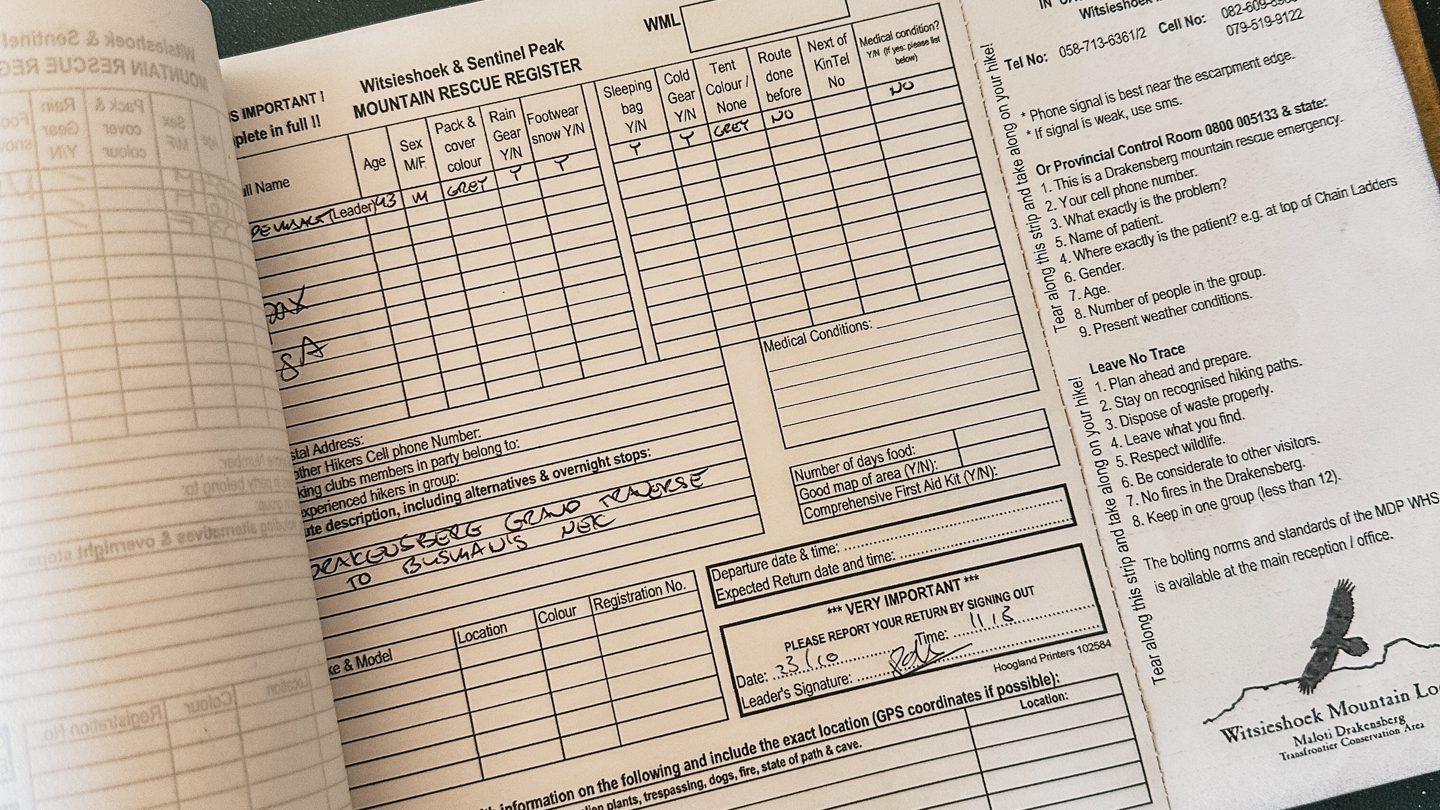

And then Sentinel Car Park. It is pretty much what it says that it is. A car park near Sentinel peak, the iconic rock peak that marks the start of the Drakensberg Grand Traverse, and quite some day hikes and other adventures (there is, for example, a nearby Via Ferrata). The car park also hosts a sizeable building with multiple not completely finished rooms (the function of which is still not fully clear to me). Upon arrival, a friendly guy asked us all to sign the Mountain Rescue Register – a way to track who is in the mountains and for what purpose (great initiative, the analogue version of the super smart Icelandic rescue setup I wrote about).

After doing that, all of us set out at different paces and with different plans. And we were welcomed with open arms by the mountain. The day was cloudy, and the clouds made the epic view even more dramatic and impressive. Just stunning. At very few moments in my life have I felt so humbled and so in awe of Mother Nature. At moments in the Faroe Islands, maybe. The vastness of the desert at Wadi Rum, perhaps. But I think that’s pretty much it. Just wow.

It was the canvas on which we made our way up, towards the famous chain ladders. It is a rather straightforward, hardened path up the mountain, with amazing views and some quirks (a micro hint of a Via Ferrata here and there with some steps, a small stairs, or a steel cable).

And then, suddenly, earlier than expected, the chainladders. The. Chain. Ladders. I’m no fan of heights. Which makes me no fan of chain ladders either. Even less so in case there was some rain and the stairs are slightly slippery, and there are some gusts of wind rattling the chains time and again.

I decided not to wait for the others, who I had left behind on our way up, chose one of the two ladders, and went.

So I did what I would recommend others as well. Just focus on the piece of ladder in front of you. Two steps up. Take the next handle. Two steps up. Next handle. Again and again and again. Do not look up. Do not look down. Just focus on the piece of ladder in front of you.

And then, faster than expected, I scaled the first ladder.

I took a deep breath and went for the second.

Same routine. Just focus on the piece of ladder in front of you. Two steps. Take the next handle. Two steps. Next handle. Again and again and again. Do not look up. Do not look down. Just focus on the piece of ladder in front of you.

I can’t say I was unhappy that it was over. Chain ladders done. Now it begins.

Day 1. The trouble begins.

I slowly but steadily made my way up the trail, getting my first glimpse of the wide open plains I would see much of in the next days. It went ok-ish. I instantly felt a bit off. You’ll know the moment you’re in a flow when you’re working or exercising. Well … I was most definitely out of whatever the flow I was looking for that day.

I tried to rule out options.

The rhythm thing could be from the trail … or better … the lack thereof. There is no trail or there are a million trails, depending on how you see it. The Drakensberg Grand Traverse is mainly a set of peaks you summit, a set of GPS coordinates you loosely follow. It requires a different kind of navigation; it requires paying more attention. Being 5 meters off might mean you’re on the wrong ridge and have to track back. On the other hand, obsessively looking for the right trail at moments will drive you mad, as there is none … or there are many. Sometimes there are clearly up to 50 different cattle and sheep tracks in parallel, sometimes it is just a vague sense of direction on a huge plain. In any case, it is often easier to get into your flow if there is a well-established trail in front of you.

By now, because of the earlier hikes, I had learned that the first day on the trail is almost always my worst day. It was the case in Greenland, where I had to settle for an inconvenient sloped camping spot, in Jordan where I had a difficult first day and camped earlier than hoped, during the Peaks of the Balkans where I just could not get my pace on the first day … it kinda feels like I need to un-city-boy-ify a bit before I can truly embrace the trail.

But that clearly wasn’t it.

I only started realizing I might be in trouble when I was making my way up Mont aux Sources, the first peak on the DGT. I couldn’t get into my normal hiking rhythm. I had shortness of breath. I felt tired. Exhausted. Even had moments when the only thing I could think of was sitting down and closing my eyes just for 15 minutes. A mini nap.

Things started to click. Cr*p. This started to look a lot like altitude sickness.

I also realised I kinda could have seen the signs. The evening before, when I had checked in at the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge, and had to walk up to my room, I also had felt slightly out of breath, but I didn’t make too much of it – must have been the travel (night flight, 5-hour drive, …) … at least so I thought.

Day 1. Consulting with the team at home.

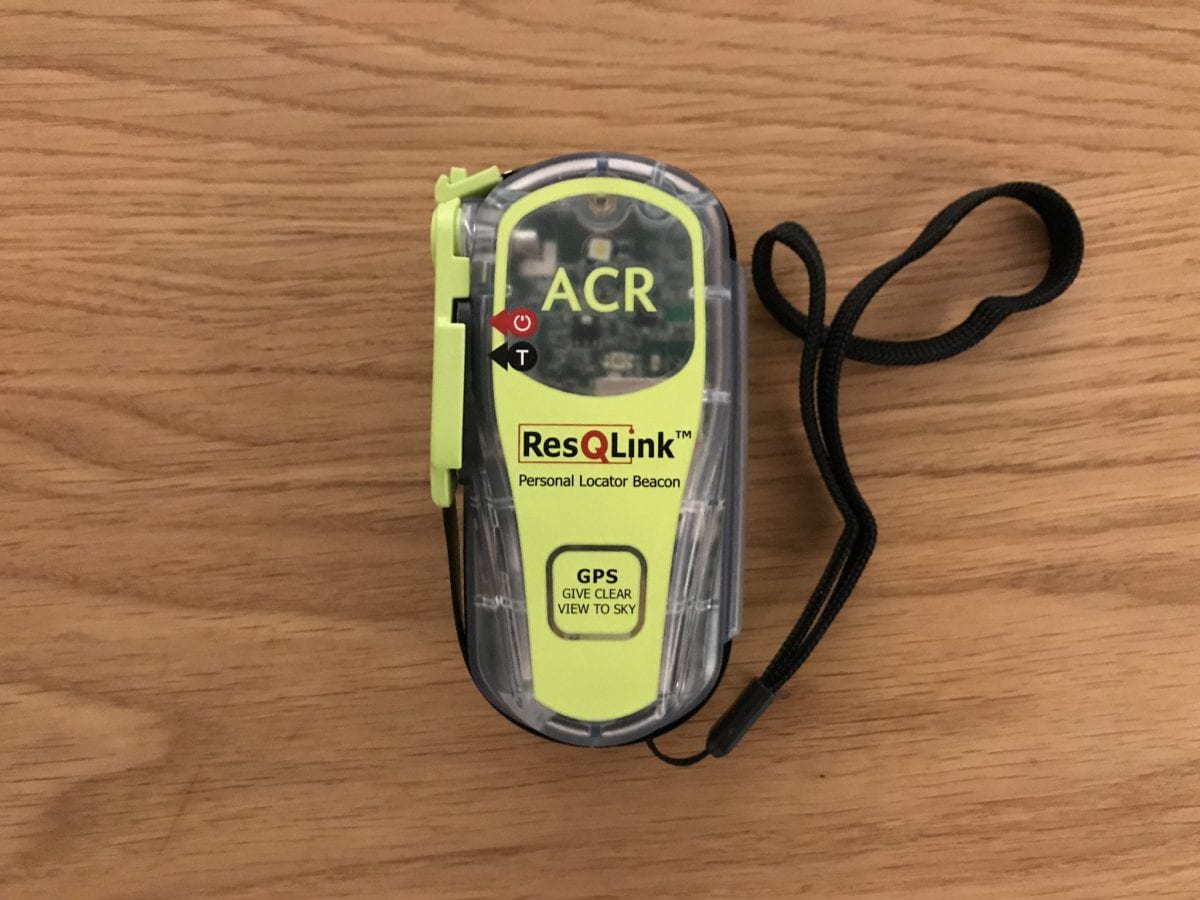

Because of experience in the past (most notably my Iceland Laugavegur trip and also just because of common sense), I keep very strict habits when it comes to communicating with the home front. First of all, I make sure I am reachable. I have my phone (obviously, but often not of much use in remote areas like the Drakensberg), I bought a new Inreach Messenger+ for this trip (which is a really strong and convenient device to enable comms through your phone or via the device itself with insane battery life) with SOS function, a Garmin GPS 67i with SOS function and even as a backup for a backup for a backup a PLB … with SOS function.

Before the trip, I also make (and made) clear agreements with my family and friends at home. Every morning when I start my hike, I check in with my GPS location. Every evening when I set up camp, I check in with my GPS location. If I miss 2 check-ins, something is really really wrong.

My new Messenger+ allowed for easy communications, so I shared my concerns and symptoms quite early on. A great way to gather second, third, and fourth opinions on the situation. We settled on me making my way to a good camping spot for the day (aiming for the valley behind Fangs saddle, ideally a bit further, to at least keep all options open for the days ahead), having a good night’s sleep, and then deciding in the morning with a fresh perspective.

The rest of the afternoon was tough. The shortness of breath remained (but luckily there were less steep climbs), and utterly exhausted, I reached the camping spot just behind Fangs saddle (which on good days would have been a late lunch spot for me) at around km 23.

For the last time that day, I admired the amazing scenery. The sun set over the hills. I made camp. Had a well-deserved freeze-dried Chicken Tikka Masala and a freeze-dried apple-crumble and fell asleep. Well … I had a night with fragmented parts of sleep … not the recovery I had hoped for.

Day 2. Waking up to a decision that was already made.

So day two became a different day two than I had prepared for months. Instead of the Hanging Valleys and an entry into the domain of Cathedral Peak, I had woken up to a frozen tent … and a big dilemma.

The complete outside of the tent was ice. As I didn’t have the pressure of a specific camping spot, I needed to make, I decided to take it easy, turn around on my inflatable mattress again and let the sun do its work. Just in case there was any last sliver of a doubt, I did a final test, hiking a bit uphill but soon found that my decision was final – there would be no DGT for me this year.

I signaled the home front that this would be the end of my attempt and that I would be making my way back. Sad for me, but relieved I had made the sensible decision. My girlfriend arranged the transfer from the Sentinel Car Park back to the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge and an extra night at the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge. I could have arranged this via my Messenger+, but some things are just way easier from the comfort of a laptop (thanks Meg!).

So, I decided to track back with an easy pace, taking in the beautiful surroundings, trying to understand more about the terrain and navigation (for another potential attempt in coming years).

The day before, I had passed a beautiful, idyllic stream and had thought how amazing it would be to camp there (but did not have the time then). So I made my way back to the stream. Only when arriving, I found that most of the ground near the stream was either covered in pollen of high grass, which would make my stay rather bumpy … or manure. When I eventually spotted that my potential camping spots were in direct sight of two shepherd huts, I decided to move on and find a more convenient spot.

The next potential spot was a bit further, near a deserted Basotho camp. The Basotho are the people of the Sotho-Tswana ethnic group, indigenous to the border area of Lesotho and South Africa, often shepherds. I did find one Basotho shepherd herding his cows nearby, and despite the camp being deserted, he made clear he would not prefer me to camp nearby (apart from that, he was very friendly and welcoming). All fine, so I picked up my bag again and set off.

It then didn’t make sense to track back on the DGT (I still had 24hrs until my transfer to the Witsiehoek Mountain Lodge, so why not take time to explore the areas), so I decided to go for a nearby trail on my GPS that connected the area where I was with Tugela Falls, which would then be my third and final option. So I set out to cover the approximately 300 meters between myself and the clearly marked trail on my GPS. And then I arrived. You guessed it … no trail. It wasn’t that the terrain was inaccessible. Far from that. It wasn’t that I needed a trail to navigate. But the trail was just not there. Anyways, I set out in the general direction, navigating an all too familiar wide plain. After crossing a saddle into Lesotho … another wide plain. A plain now that let me finally get a glimpse of the Bilanjil Falls, the fact that probably a fellow Dutchie had made his/her way up here, and the Tugela Falls area.

An unexpectedly nasty climb was between me and my camping spot at Tugela Falls, but the curious and playful group of wild baboons playing and keeping a close eye on my progress made it all worthwhile. And after crossing the hill, I finally had a clear view over the Tugela river valley, a majestic sight.

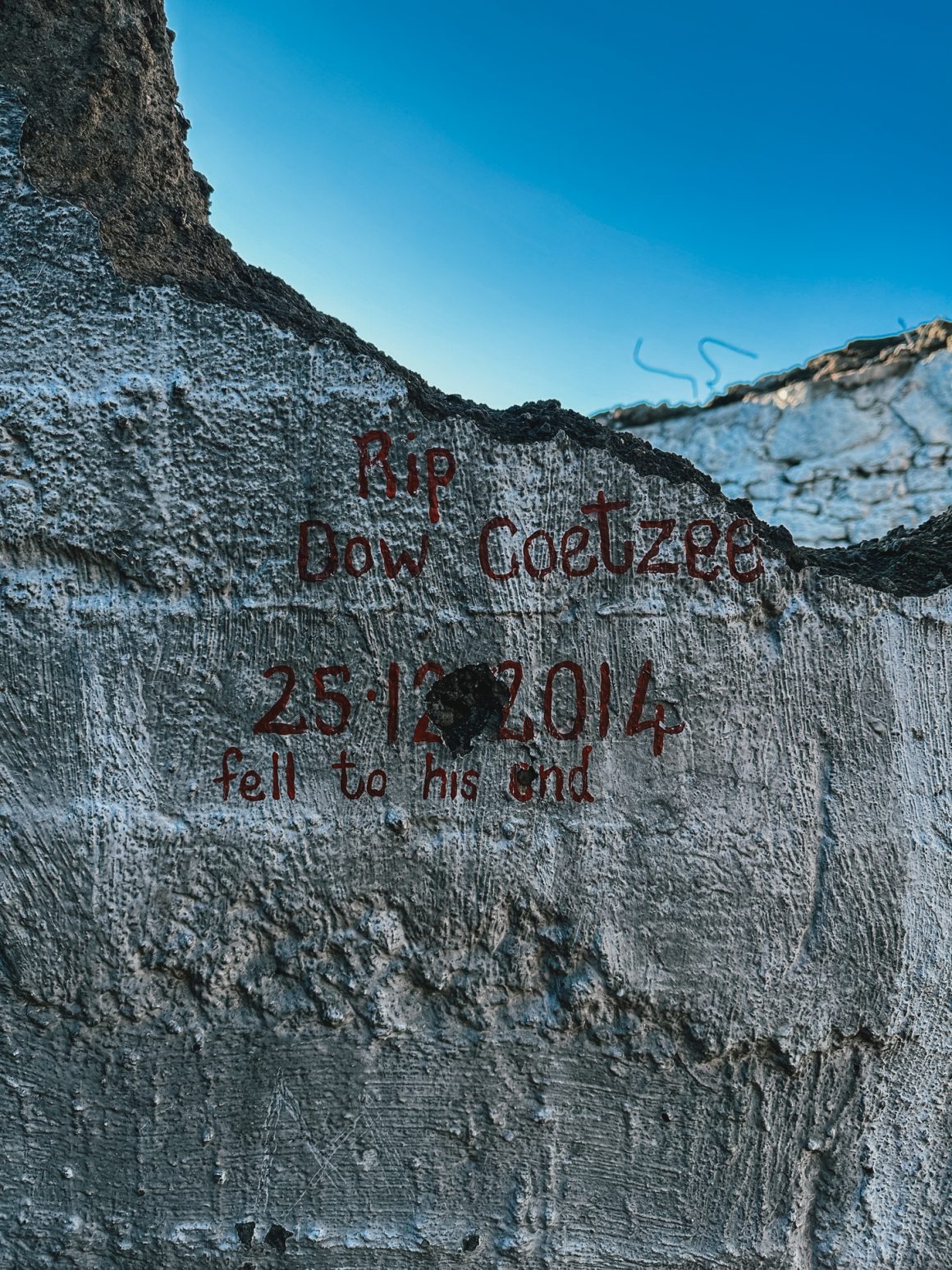

I had briefly considered sleeping in the Tugela River hut, but found the hut at the Tugela River in a shocking state. Half of the roof was blown off. It was filthy. One of the rooms was full of garbage, and it was hard not to think that at least the two brand new bottles that were there were leftovers from the four locals I had met the day before. So, navigating and avoiding shards of glass spread out over the area near the hut, I finally found a spot that was safe enough to lay my air mattress without it getting punctured. A stark reminder of how we as humans are so well capable of turning each and every part of nature into a filthy mess.

Day 3. Tapping out.

The night was horrible. Again. I must have seen every single hour on the clock. My body didn’t seem to be able to relax, to let go. It was frustrating to doze off, be wide awake later, be utterly convinced you slept for hours, only to see you slept for 45 minutes, an hour tops. I was just really happy that it was not the night before entering the infamous Cathedral Peak area of the DGT.

So I took it easy in the morning. The transfer to the lodge would be waiting for me at 12h30, which gave me pretty much all morning for about 8 kilometers. So I took my time to breathe in the quietness and beauty of the trail for the last time.

As I was closest to the so-called “gully” descent towards Sentinel Car Park, I chose the gully over another confrontation with the chainladders. I had heard from some that they found the gully descent very difficult and dangerous. I can’t say it was super easy, and I can imagine that after heavy rainfall, the slippery stones can make for a formidable hurdle, but in normal weather, it felt totally doable.

So, I made my way down, and then I was snapped back to reality. I had set foot on the trail to/from Sentinel Car Park again, and that meant I was back in the world of day tourists. Within 10 minutes, I had encountered my first group of elderly French day hikers. 45 minutes into my final descent to the car park, I had parked on the side of the trail for two other big groups (one group of Germans and one international group with a large contingent of Indians) and 3 smaller groups.

And then there was no way back. The Sentinel Car Park. I signed out of the Mountain Rescue Register. Which may have been the most emotional part of the whole experience. There it was. Black on white. Official. I had lost. I had failed. The mountain had won. Drakensberg 1. Polle 0.

Final note: I hope you won’t need to tap out, but just in case: the tap-out experience is great. The Sentinel Car Park team welcomed me with open arms. I could use the water supply (the large blue tank behind the building on the left (completely behind, there are two other tanks before)), could use the wifi, and we chatted a bit while I shared some of my leftover candy and donated the gas-cannisters I didn’t need anymore for future hikers. Thanks guys!

What I learned from my failed attempt of the Drakensberg Grand Traverse.

When writing this, three days have passed since I tapped out, and I had some time to reflect and talk to friends and family. The first question I usually get is … will you try again? And yes. It feels I *need* to be back. It feels like unfinished business. The (too) limited time on the trail has left an eternal mark.

Reflecting further, I think these are my key learnings and take-aways.

- I am not a spiritual man, but mountains make me spiritual. I think what will stick with me most is that the mountains have a soul; they are alive. They give and take. You’re a mere humble guest in their home. The moment you get arrogant, cocky, or think you’ve got things sorted out, the mountains will find ways to make you humble. Next to that, being alone with nature, reconnecting with nature, is an extremely refreshing, rewarding and rejuvenating experience. It is hard to describe the joy of having your feet in a fresh mountain river after a long day in nature with nothing surrounding you apart from some chirping birds. A reminder again for myself, I need the trail in my life … too long away from the trail will make me homesick for the trail.

- Prepare and then some. And plan for the worst, hope for the best. Even supported and with a group, the Drakensberg Grand Traverse is a very serious challenge. Anything can happen in the mountains, including the famous Drakensberg end-of-day showers and storms. It took me months and months to prepare, gathered quite some experience over the years and I must have packed, unpacked and re-packed my bag a dozen times … but still, I could have done more and had made some mistakes (e.g. it turned out I brought lens fluid and 2 extra lighters I didn’t need, but forgot to take my buff). To be frank, the Drakensberg Grand Traverse is probably right on the limit of what I am personally capable of. Next time, even more prep.

- The Drakensberg escarpment is high, very high. I got beaten by altitude sickness. So I need to acclimatize better next time. That means extra days on 2500-2750 meters. And extra “buffer” days at the end in case/when things go wrong and your planning gets delayed. I did not have the luxury now to take it easy and spend more time in the mountains acclimatising. I heard about ginger helping in higher altitudes. There are definitely other things I can and should do. I need to figure this out before I can even think about another attempt.

- Again. The Drakensberg escarpment is high, very high. I underestimated some side effects of the altitude. like the UV strength of the sun on higher altitudes. Despite applying sunscreen 2-3 times per day with factor 50+, I still got some serious sunburn. Next time, even more prep.